The landscape of alternative proteins is undergoing a seismic shift, moving decisively into what industry pioneers are terming Plant-Based 3.0. This new era transcends the simple imitation of meat textures with isolated proteins and starches, focusing instead on creating whole-muscle analogues with complex, fibrous architectures that genuinely mirror the eating experience of animal meat. At the vanguard of this revolution are two powerful biological workhorses: mycoprotein and microalgae. The technological race is no longer just about ingredient sourcing; it is fiercely centered on the sophisticated art and science of texturization—transforming these microbial biomasses into convincing steaks, fillets, and chunks.

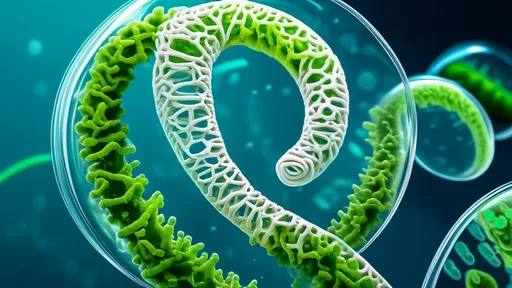

Mycoprotein, a filamentous fungal protein most famously associated with the brand Quorn, has a decades-long head start. Grown in large-scale fermenters through a process akin to brewing, the fungus Fusarium venenatum naturally produces a microscopic, interconnected network of hyphae. This innate mycelial structure is the foundation of its meat-like texture. The historical challenge, however, has been scaling the post-fermentation processing to create larger, coherent, and anisotropic (directionally oriented) structures that mimic whole cuts of meat, rather than just restructuring the biomass into homogeneous patties or grounds.

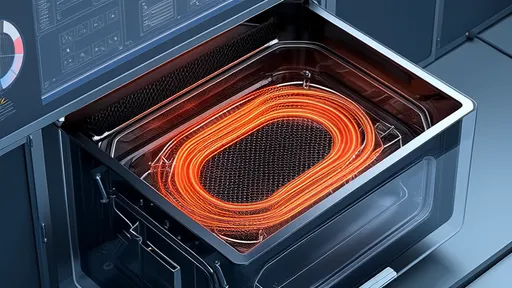

Emerging technologies are meeting this challenge head-on. Advanced extrusion techniques are being refined to handle the delicate fungal filaments. High-moisture extrusion cooking (HMEC) is particularly promising. Here, the mycoprotein slurry is subjected to precise combinations of heat, pressure, and mechanical shear in a specialized extruder. As it exits the die, the sudden drop in pressure causes the protein melt to expand and align, forming layered, fibrous textures that are remarkably similar to chicken breast or pork loin. Companies are now developing multi-step, multi-stream extrusion processes that can co-extrude different protein blends or even incorporate fats and marbling in situ, creating a more authentic and juicy consumer product.

Beyond extrusion, other novel texturization methods are gaining traction. Shear-cell technology, which uses a system of rotating cones to gently align protein particles under shear stress, is being adapted for mycoprotein. This method is celebrated for its energy efficiency and its ability to create larger and more defined fibrous structures compared to traditional extrusion. Furthermore, 3D food printing offers unparalleled precision. By using mycoprotein-based edible inks, printers can deposit material layer by layer, programming not only the macroscopic shape of a cut but also the microscopic directionality of the fibers and the precise placement of fat and connective tissue analogues. This digital manufacturing approach allows for ultimate customization, paving the way for designer cuts of meat tailored to specific culinary applications.

While mycoprotein operates on a fungal scale, the world of microalgae presents a different set of opportunities and hurdles. Species like Chlorella, Spirulina, and Nannochloropsis are nutritional powerhouses, packed with protein, essential fatty acids, and micronutrients. However, their unicellular nature means they lack any inherent fibrous structure. Transforming a slurry of microscopic algal cells into a chewy, tearable steak is the paramount technical obstacle in the algae protein space. The raw ingredient often comes with strong pigmentation and distinct savory, sometimes umami-rich, flavor profiles that must be carefully managed during processing.

The texturization of algal biomass is a field of intense innovation. Researchers are exploring specialized extrusion processes that can force the algal protein to denature and cross-link into continuous matrices. Binding agents, both protein-based and polysaccharide-based, are crucial in helping the individual cells cohere into a unified structure. Some companies are pioneering hybrid approaches, using algal protein as a high-nutrient booster within a mycoprotein or pea protein matrix, leveraging the structural benefits of the latter while enhancing the nutritional profile with the former.

Perhaps the most cutting-edge approaches involve bottom-up assembly. Scientists are experimenting with techniques like electrospinning, creating nano-fibers of algal protein that can be woven into larger scaffolds. Cultivation methods are also being tweaked; some startups are exploring stressed growth conditions that encourage certain microalgae to produce more exopolysaccharides, natural biopolymers that can act as internal binders and improve the texture of the final biomass even before processing begins. The goal is to move from a paste-like consistency to a firm, sliceable, and cookable material.

The drive towards Plant-Based 3.0 is fueled by a powerful confluence of consumer demand, environmental necessity, and investment momentum. Modern consumers are increasingly flexitarian, seeking products that deliver on taste, texture, and nutrition without compromise. They are more ingredient-aware and skeptical of overly processed foods, which puts a premium on clean-label production methods like fermentation. The sustainability argument is more potent than ever; microbial cultivation requires a fraction of the land and water used for traditional livestock and can be conducted vertically in bioreactors, decoupling food production from environmental degradation and climate volatility.

This has unlocked unprecedented levels of investment. Venture capital is flowing into biotech startups focused solely on strain optimization, fermentation scale-up, and novel texturization technologies. Major food conglomerates are establishing dedicated R&D divisions and forming strategic partnerships with these agile innovators, recognizing that the future of protein is being built in labs and pilot plants. The regulatory landscape is also evolving, with agencies like the FDA and EFSA creating clearer pathways for novel food approvals, providing the certainty needed for large-scale commercialization.

Despite the exciting progress, the path forward is not without its obstacles. Scaling these sophisticated texturization technologies from the lab bench to cost-effective, high-volume industrial production remains a formidable hurdle. The capital expenditure for large-scale fermenters and specialized extrusion lines is significant. Consumer acceptance is the ultimate test; while early adopters are enthusiastic, winning over the mass market requires achieving price parity with conventional meat and delivering an indistinguishable sensory experience. There is also the ongoing task of consumer education to overcome the "yuck factor" sometimes associated with fungus and algae, repositioning them as premium, sustainable, and delicious ingredients.

The journey into Plant-Based 3.0, powered by mycoprotein and microalgae, represents a fundamental reimagining of how we produce protein. It is a shift from agriculture to fermentation, from field to bioreactor, and from simple grinding to complex structural fabrication. The success of this transition hinges on the continuous refinement of texturization technologies—the ability to architect taste and mouthfeel at a microscopic level. As these technologies mature and scale, they promise to redefine the very center of the plate, offering a future where the most sustainable and ethical choice is also the most delicious and satisfying.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025