When selecting cookware for the kitchen, one of the most critical yet often overlooked factors is the thermal conductivity of the material from which the pot or pan is made. Thermal conductivity refers to a material's ability to transfer heat from the heat source—be it a gas flame, an electric coil, or an induction hob—through the body of the cookware and into the food. This property is paramount because it directly influences how quickly and evenly a pan heats up, how it responds to changes in temperature, and ultimately, how much control a cook has over the cooking process. Among the plethora of materials available, copper, aluminum, and cast iron stand out as three of the most common and historically significant, each possessing distinct thermal characteristics that cater to different culinary needs and techniques.

Copper is, without a doubt, the undisputed champion of thermal conductivity in the kitchen. With a thermal conductivity rating of approximately 401 W/m·K (Watts per meter-Kelvin), it outperforms nearly all other metals used in cookware. This exceptional property means that when heat is applied to a copper pan, it is distributed across the entire cooking surface almost instantaneously. There are no significant hot spots; the entire base of the pan reaches a remarkably uniform temperature. This is a godsend for tasks requiring precise temperature control, such as making delicate sauces, tempering chocolate, or searing a piece of fish to perfect doneness without overcooking. The pan responds to adjustments in the burner's heat with lightning speed, giving the cook unparalleled command.

However, pure copper has two significant drawbacks. Firstly, it is a highly reactive metal. When it comes into contact with acidic foods like tomatoes, wine, or vinegar, it can leach into the food, imparting a metallic taste and, in large quantities, posing a health risk. Secondly, pure copper is exceptionally soft and prone to scratching and denting. To combat these issues, most high-quality copper cookware is lined with a non-reactive metal. Traditionally, this was tin, which has a very low melting point and requires careful, gentle use. Modern copper cookware is almost exclusively lined with a thin layer of stainless steel, combining the superb heat conduction of copper with the durability and non-reactivity of steel. The main trade-off, of course, is cost; this combination of premium materials and often hand-hammered craftsmanship makes copper cookware the most expensive option on the market.

Aluminum is the workhorse of the commercial and home kitchen, prized for its excellent balance of performance and affordability. With a thermal conductivity of around 235 W/m·K, it is a very efficient conductor of heat, second only to copper among common cookware metals. Like copper, it heats up quickly and distributes heat quite evenly, making it a reliable choice for a wide array of cooking tasks, from boiling water to sautéing vegetables. Its lightweight nature is a significant advantage, making large pots and pans easy to handle. For these reasons, aluminum is the core material in the vast majority of clad stainless steel cookware (e.g., All-Clad), where a thick aluminum layer is sandwiched between two layers of stainless steel to provide the even heating that stainless steel alone lacks.

The primary weakness of aluminum, similar to copper, is its reactivity. Uncoated aluminum will react with acidic and alkaline foods, which can cause discoloration of the cookware and off-flavors in the food. To make aluminum suitable for everyday cooking, it is almost always treated. The most common treatment is anodization, an electrochemical process that hardens the surface of the aluminum and creates a non-reactive, non-stick layer that is much more durable than traditional non-stick coatings. Anodized aluminum cookware is exceptionally hard, resistant to scratching, and completely non-reactive, solving the metal's core deficiencies while retaining its excellent conductive properties. Another popular treatment is simply coating the aluminum in a non-stick material like PTFE (Teflon), though these coatings are less durable over the long term.

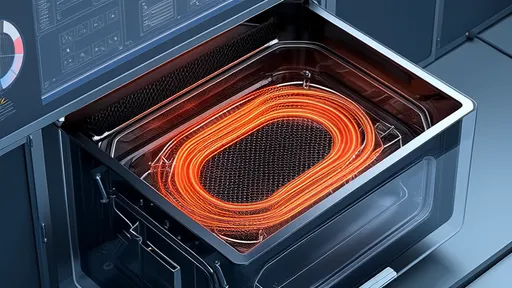

Cast iron occupies a unique and beloved place in the culinary world. Its thermal properties are the inverse of copper and aluminum. With a thermal conductivity of only about 55 W/m·K, it is a relatively poor conductor of heat. It heats up slowly and unevenly at first; if placed on a small burner, a distinct hot spot will form directly over the flame. However, once heated, cast iron possesses an incredible ability to retain that heat due to its very high volumetric heat capacity. It is a heat reservoir. This makes it exceptionally stable and excellent for tasks where consistent, radiant heat is desired, such as searing a steak, baking cornbread, or frying chicken. It holds its temperature even when a cold piece of food is added to the pan.

The legendary status of cast iron is also built on its unparalleled durability. A well-made cast iron skillet can literally last for centuries and be passed down through generations. Its maintenance, however, is a topic of much discussion and tradition. It requires seasoning—a process of baking a thin layer of polymerized oil onto its surface—to create a natural, non-stick coating and to protect it from rust. Unlike the non-stick coatings on aluminum pans, this seasoning can be repaired and renewed by the user indefinitely. While modern enameled cast iron (like Le Creuset) eliminates the need for seasoning by coating the iron in a glass-like enamel, traditional bare cast iron is prized for the character and improved non-stick performance that develops over years of use and care.

In a direct comparison of pure thermal efficiency, the hierarchy is clear: copper is the fastest and most even conductor, followed closely by aluminum, with cast iron being a distant third. But this simple ranking tells only part of the story. The "best" material is entirely dependent on the application. A French pastry chef making a delicate butter sauce would find copper indispensable for its precision. A home cook preparing a weeknight stir-fry might find anodized aluminum or clad aluminum cookware to be the perfect blend of responsiveness, even heating, and easy cleanup. A barbecue enthusiast looking for the perfect sear on a ribeye would swear by the relentless, steady heat retention of a heavy cast iron skillet.

Ultimately, the choice between copper, aluminum, and cast iron is not about finding a single winner but about understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each material. It is about matching the tool to the task. Many serious cooks and professional kitchens do not rely on a single type of cookware but instead maintain a battery of pots and pans, each chosen for its specific thermal properties. They might reach for a copper saucier for a hollandaise, a clad aluminum sauté pan for onions, and a cast iron Dutch oven for a long-braised stew. This holistic approach allows them to harness the unique thermal conductivity of each material to achieve the best possible results in every dish they create.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025