In the dim light of ancient fires, our ancestors tore meat from bone with their teeth and hands, sharing not just sustenance but the very essence of social bonding. This primal act of commensality—eating together—laid the foundational stones for what would become one of humanity’s most complex and revealing social rituals: the shared meal. Across millennia, the table has transformed from a simple surface for consumption into a stage where social contracts are performed, negotiated, and evolved. The anthropology of eating together reveals that table manners are far more than arbitrary rules of etiquette; they are the visible expression of deeply ingrained social agreements that dictate hierarchy, trust, reciprocity, and cultural identity.

The earliest evidence of communal eating points to its role as a mechanism for social cohesion. In hunter-gatherer societies, the distribution of food was not merely a matter of survival but a critical act of political and social significance. The individual who procured the food—often the successful hunter—would oversee its division, reinforcing their status and ensuring equitable sharing to maintain group harmony. This act was a primitive yet powerful social contract: the provider demonstrated generosity and leadership, while the recipients acknowledged their dependence and solidarity. Failure to share could mean ostracism, a death sentence in environments where collective effort was essential for survival. Thus, the roots of table manners are found not in refinement, but in the raw necessity of cooperation and mutual obligation.

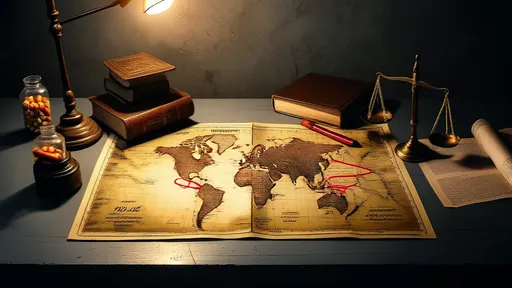

As human societies grew more complex, transitioning from nomadic bands to agricultural settlements and eventually to stratified civilizations, the rules governing shared meals evolved in tandem. The act of eating together began to serve new functions: it became a tool for displaying wealth, reinforcing social hierarchies, and negotiating power. In ancient Sumer, Egypt, and China, elaborate feasts were hosted by rulers and elites. These were not just celebrations but political theater. Seating arrangements, the order of service, the quality and type of food offered to different guests—all were meticulously designed to reflect and reinforce the social order. To be invited was a sign of inclusion in a privileged circle; to be seated near the host, a mark of high honor. The social contract here was explicit: loyalty and service in exchange for patronage and protection. The table became a map of the social world, and manners were the code by which one navigated it.

With the rise of classical civilizations, particularly in Greece and Rome, commensality took on philosophical and cultural dimensions. The Greek symposium, for instance, was a ritualized drinking party that followed a meal. It was governed by strict rules—a symposiarch to mix the wine and water, prescribed topics of conversation, and rituals to honor the gods. This was not mere revelry; it was a formalized space for intellectual exchange, political debate, and the cultivation of social bonds among elite men. The contract was one of mutual intellectual and moral enrichment. Similarly, in Rome, the cena (dinner) was a key social institution where patrons and clients met, business was conducted, and alliances were forged. Table manners, such as reclining on couches in a specific order, using certain utensils, and employing napkins, were markers of civilization and status. To violate these norms was to reject the very fabric of Roman society.

The medieval period in Europe further entrenched the connection between table manners and social structure. The great hall of a castle was a microcosm of feudal society. The lord and his family dined at the high table, elevated and often on a dais, while knights, servants, and retainers sat below in descending order of rank. Meals were served with elaborate ceremony, and specific codes of conduct—such as the use of trenchers (stale bread used as plates), shared cups, and rules about hand-washing—governed every action. These practices reinforced the hierarchical contract of feudalism: protection and sustenance from the lord in exchange for service and loyalty from the vassals. The introduction of courtesy books in the Late Middle Ages, such as those instructing one not to spit on the table or gnaw on bones and then put them back in the shared dish, marked a growing awareness of the body and a shift towards self-regulation and civility.

The Renaissance and the early modern period witnessed a revolution in table manners, driven by the influence of the Italian courts and the broader cultural movement towards individualism and refinement. The widespread adoption of the fork, initially viewed with suspicion as an effeminate or sacrilegious instrument, revolutionized eating practices by further distancing the diner from the food. New utensils, individual plates, and glasses emerged, reducing the need for sharing and emphasizing personal space and hygiene. This period also saw the proliferation of etiquette manuals, like Erasmus of Rotterdam’s On Civility in Children, which disseminated new codes of conduct across Europe. The social contract was evolving from one based purely on public hierarchy to one that also valued personal discipline, bodily control, and the cultivation of a courteous self. Good manners became a currency of social mobility, a way for the rising bourgeoisie to signal their worth and aspire to elite status.

The Enlightenment brought a philosophical shift, framing manners as part of a broader social contract theory. Thinkers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau debated the role of education and socialization, with Locke emphasizing the importance of cultivating good manners to create polite and cooperative citizens. The meal table became a training ground for the virtues required by civil society: self-restraint, consideration for others, and respect for shared norms. The 18th and 19th centuries, with the rise of the middle class and the Victorian era, codified table etiquette into an intricate and often bewildering system of rules. Everything from the arrangement of countless utensils to the language used to request food was prescribed. This hyper-formality served as a barrier, a way for the established upper classes to protect their status and for the nouveau riche to anxiously learn the codes of admission. The contract was one of exclusion as much as inclusion, defining insiders and outsiders with crystal clarity.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, globalization and technological change have dramatically altered the social contracts of the table. The strict formalities of the Victorian era have largely relaxed, reflecting more egalitarian social ideals. The family dinner, once a daily ritual reinforcing patriarchal authority, has transformed in structure and frequency. Yet, new rules have emerged. The allergy alert, the vegan preference, the gluten-free request—these are modern manners that negotiate a new contract of mutual care and respect for individual bodily autonomy and identity. The "phone stack" before a meal, where friends pile their devices to discourage distraction, is a novel social agreement to prioritize human interaction in the digital age. Furthermore, the global fusion of cuisines and dining practices demands a new cultural sensitivity, a contract of cross-cultural respect and curiosity.

From the primal sharing of a hunt to the silent agreement to not check a notification during dessert, the evolution of table manners is a continuous renegotiation of the human social contract. It is a story of how we have continually reshaped the act of eating together to reflect our changing values: from survival-based reciprocity to hierarchical display, from civilizing self-control to individual expression and global citizenship. The table remains a powerful forum where we perform, and ultimately define, our relationships to each other and to the societies we build. The next time you pass a dish, wait your turn, or choose your words at dinner, remember you are participating in a ancient and ever-evolving ritual—one bite at a time.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025